The emergence of native nesting bees are a welcome sign of spring in the Northwest. There are upwards of 100 species of native bees just in the Portland area, yet many are largely unknown compared to the non-native honey bee. Most native bees are smaller, solitary – and therefore not aggressive and not a threat to people – and tend to get overlooked. But in fact, native bees are often more efficient pollinators for crops and flowers and critical for a healthy ecosystem.

Unfortunately, bees and other insects across the world are in decline due to pesticide use, climate change, disease, and habitat loss. Bees and other insects like butterflies, beetles, flies, and even wasps are important pollinators for many of our agricultural crops and other flowering plants. While there has been growing public awareness of the need to conserve pollinators, often the focus has been on the few species used in commercial agriculture and less emphasis has been placed on providing appropriate nesting sites and resources for our lesser-known native bees.

Residents are inspired to create bee nesting habitat to help slow this decline, and they want to know how best to do this. However, scientists and the conservation community lack basic necessary information on numerous species of bees. In many regions, scientists do not even know what species of bees are present. This makes it difficult to develop guidelines for bee conservation.

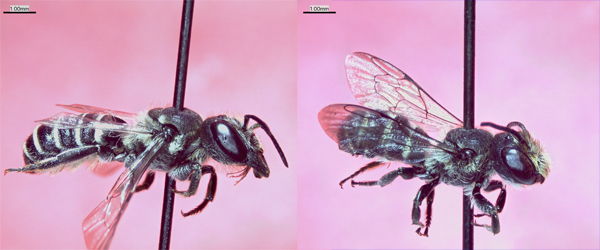

Last fall, we talked to Stefanie Steele about her research on nesting bees in Portland, Oregon. Steele investigated how and where native cavity nesting bees make their nests. The majority of bees nest in the ground, and about 30 percent nest in cavities. Steele’s research focused on the nesting height and diameter preferences of solitary cavity nesting bees that use wood or plant cavities above ground, versus those that nest underground by mining into the soil. Specifically she looked to answer these three questions: What cavity nesting species are present in the greater Portland, Oregon area? What cavity nesting widths do species use? And what nesting heights do species use?

“To effectively conserve bee communities, we first need to know what species are here and how and where they nest and what they need to survive,” Steele explains. “Most bees are collecting materials to bring into the nest, like mud, petals, pebbles, and plant materials, therefore we need to learn what to provide. Nesting research data will help residents of greater Portland know how best to provide habitat for cavity nesting bees.”

She recently completed her Master’s in Science at Portland State University and shared results of her research. The study placed nests at 0.5 meter, 1.5 meters, and 2.3 meters above the ground. Overall she found that cavity nesting bees used all three of these nest heights, but did not have a preference for height. Therefore, cavity nests should be made available at varying heights, similar to naturally occurring cavity nests in logs, stumps, snags, or stems. Of the cavity widths that were tested – 3, 5, 6, 8 & 10 millimeters – all sizes were used. The 3 mm and 5 mm wide cavities were used most by a variety of bee and wasp species. (Read the full thesis to find detailed methods, results, and many more incredible photos!)

Here are a few tips for creating bee habitat where you live:

Blue orchard mason bees are one of Portland’s many mason bees or Osmia species. Blue orchard mason bees are only active in the spring and will use a range of a cavity sizes, including 5, 6, and 8 mm width holes (diameters), and they are opportunistic. Steele even found some nesting in her wind chimes! Despite what many people think, it’s not necessary to bring cocoons or nests inside for winter. However, with a new invasive cleptoparasitoid fly, the Houdini fly, found in the Pacific Northwest, mason bee nests should be checked for these flies. See the Washington State Department of Agriculture page for more information on how to recognize these flies and actions you can take.

Other cavity nesting bee species like many of the leaf-cutter, wool carder, resin, and cellophane bees often are smaller bodied than the blue orchard mason bee. They are primarily active during the summer months, so it is important to provide cavity nesting sites in a range of sizes and offer a variety of different kinds of flowers throughout the summer season for these bees.

Tip: Providing ample nesting opportunities in various places can allow cavity nesting bees to spread out and be less impacted by parasitoids and predators that might devastate a single nest site. If you are building a nest box, use thicker wood on the sides to prevent wood from warping from moisture. Trapped or increased moisture in wood, or in plastic tubes, can lead to mold and will be less attractive to bees.

Cavity nesting wasps should be welcome residents in your garden! These wasps hunt insects (aphids, caterpillars, crickets) and spiders to feed their young. Gardeners often consider these insects pests, so the biocontrol service provided by these wasps can be very beneficial. Solitary cavity nesting wasps used all five cavity sizes, but used 3 mm cavity widths the most.

Small carpenter bees will chew tunnels in pithy plant stems like asters (Symphyotrichum spp.), raspberry (Rubus spp.), and elderberry (Sambucus spp.), for example. Cut stems at the end of winter to at least 6-8” tall and leave them standing through at least the following spring and summer. New plant growth will grow around the cut stems and eventually the cut stems will decompose on their Learn more about creating habitat for stem-nesting bees.

Mining bees and sweat bees are some of Portland’s most abundant ground nesting bees. Many require bare ground to nest, but some will also nest in grass or mix vegetation lawns. Bare soil is an important resource for these bees, as well as cavity nesting bees who use mud to build their nest cells.

Bumblebees will often use pre-existing holes in the ground, such as abandoned rodent burrows, and others will nest in pre-existing cavities above ground, such as in a tree or even an unoccupied bird house.

Want to drill holes in a snag or downed log? Use these size drill bits to replicate the diameters that Steele studied, and make a hole about 6 to 8 inches deep: 3mm = 1/8”; 5mm = 3/16”; 6mm = 1/4”; 8mm = 5/16”; 10mm = 3/8”

Embrace a “messy” natural garden year-round! Leave the leaves, sticks, and logs on the ground. Leave cut stems sticking up and allow new stems to grow in a “winterscaped” landscape. Clear a few small areas to expose bare ground. Consider replacing lawn with native plants. Perfectly manicured lawns are not good habitat. Natural areas and features allow for many more opportunities for bees to find just the right spot to make a nest.