(Photo by Nicholas T: www.flickr.com/photos/nicholas_t/11660023586)

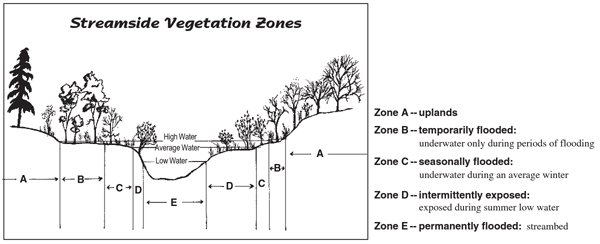

One of the most essential types of natural habitats we have is the riparianRiparian areas The land alongside a stream, creek, river, or floodplain forest, which affects the health of the adjacent stream and benefits our climate. A riparian forest is the community of trees, shrubs, and understoryUnderstory The area under and around trees plants adjacent to a stream or body of water. The plants closest to the stream are adapted to moist soil conditions and those species a bit further away tolerate a middle ground between wet and dry conditions. They comprise various zones, as shown in this graphic.

Riparian forests provide important pathways for wildlife to move through the landscape and to higher, cooler areas. Trees and other vegetation along streams, and elsewhere, are key to storing carbon and keeping air and stream temperatures lower, which we will need more and more as the global climate warms. Have you ever gone into the forest on a hot day and noticed how it’s 20 degrees cooler? If so, you’ll appreciate how invaluable are the shade and moisture retention that our forests provide. We also need trees and shrubs to capture and store rainwater that is hitting us in higher volumes during increasingly intense winter and spring storms. (Remember the “atmospheric riversAtmospheric rivers A band of clouds that moves through the atmosphere capable of carrying and dropping massive amounts of rain” we experienced this fall?) The more we collectively preserve and plant such vegetation, the more benefits we’ll see. Here are 5 tips for creating and maintaining a healthy riparian forest and a healthy stream:

1. Plant and preserve native trees and shrubs along your stream. Not only do they shade the stream, which helps keep the water cool for fish and other aquatic life, their roots hold onto the soil and minimize streambank erosion. They filter pollutants from run-off water, slow its movement across land, and help recharge ground water. With our increasingly dry, hot summers, ground-water recharge is more important than ever before.

Look for local sources of plants to get species adapted to your growing conditions and local wildlife needs. You can use a Willamette Valley retail or wholesale nursery that specializes in native plants, or harvest “starts” of plants off your land or where you have permission. You can cut off branches of willow, red-twig dogwood and cottonwood trees in the late fall – right now! – and just stick them into moist streambanks. Strive for cuttings that are 2-3 feet long and insert them half to two-thirds of the way into the ground, with the buds facing up. Assuming conditions are right, they will root and grow, like magic! You can also dig up small seedlings of other suitable plants, such as western red cedar, Oregon ash, or red or white alder, where you have many and move them to your streamside areas. Look around for what likes to grow near your stream and, once you’ve confirmed those species are native, plant more of them.

See the Guide for Using Willamette Valley Native Plants Along Your Stream for appropriate species and for tips on how to propagate your own plants from cuttings.

2. Plant and care for understory species in your riparian area. These might include native shrubs and small trees like cascara, Douglas hawthorn, snowberry and salmonberry, or twinberry and Douglas spirea for sunny edges or openings. A mix of woody plants contributes to a good matrix of roots under the ground that hold the soil in place. They also support and benefit from soil life such as fungi, and provide much needed food for birds, pollinating insects, and other wildlife. Flowering plants, in particular, provide nectar and pollen for bees and hummingbirds, but most plants attract native insects. Since insects are the bottom of the food chain, plants that support them support other wildlife. Some native trees, like Western hazelnut, even provide nuts as food for jays and squirrels, for example.

(See here for local sources of native plants: https://emswcd.org/native-plants/local-sources/)

3. Add native grasses and wildflowers that naturally occur in riparian areasRiparian areas The land alongside a stream, creek, river, or floodplain. Blue wildrye is an example of a locally common native grass that tolerates sun and shade, and it can be purchased inexpensively by the pound. Tufted hairgrass is a great native species for moist, sunny areas. You can also add wildflowers that like understory settings, such as largeleaf avens, fringe-cup, and youth-on-age. Really moist soil areas can benefit from native sedges, rushes and bulrushes, like small-flowered bulrush and slough sedge. Try digging up and transplanting a few or getting some from a local nursery, as with the wildflowers. Scatter seed of native grasses where you have bare soils areas, particularly if you’ve cleared an area of invasive blackberry or reed canary grass.

Free up more areas for native seed and native plants by controlling invasive weeds. Along with reed canary grass (RCG), tackle aggressive herbaceous invaders such as shiny geranium, which can take over the ground of a riparian area. Keep reed canary grass somewhat at bay with persistent cutting, combined with heavy, heavy mulch. Be aware, however, that too much mulch applied where it can wash into the stream is not a good thing. Remove RCG growing immediately around desired plants – either manually or with careful use of herbicide – and have patience while new native trees and shrubs grow up and gradually shade it out. The goal is to avoid the intense competition for water and nutrients the RCG imposes.

4. Retain downed “wood” that ends up in or near streams. When trees lose branches and fall near or across a stream, they shed leaves and twigs that become food for aquatic insects and other critters, such as crayfish, that live in streams. The downed logs end up creating pools where fish hold and take cover from predators and where the deeper water created is nice and cool. The wood that falls on land will decay and provide future organic matter and healthy soil, which will harbor a wide range of life and be more hospitable to future plant growth. And while the log is still intact, it can shade and help fragile new seedlings establish. Also, while it’s not a guarantee, beaver may use downed pieces of wood for dam-building instead of cutting new, growing pieces.

5. Consider the benefits of beaver for water retention and fire breaks. Recent experience in Oregon has shown that beaver-flooded areas are extremely resilient to wildfire and serve as both important fire breaks and refuge areas while fires rage. After a fire, a green oasis is left behind. If beaver are taking more trees than you’d like, you can create wire “cages” around key trees to preserve them. You can also plant trees and shrubs adapted to beaver browse, like dogwood, cottonwood, and willows, which generally grow back after being browsed. (Our native willows include Pacific, Sitka and Scouler’s willow, the latter tolerating the driest of conditions.) Or select plant species that are less preferred by beaver, like Pacific ninebark, elderberry, and swamp rose. If you want to learn more about how beaver can benefit a stream, watch this recent video by the Oregon Zoo, or this one by Oregon Public Broadcasting.

So, there you have it. Keep and plant more native plants near your stream, control invasive weeds, propagate your own plants on-site to save money and have hyper-adapted plants, embrace a “messy” natural riparian area with downed wood and beaver, if you can, and promote a variety of plant species and types. Work with your neighbors to maximize benefits. We suggest a 50-foot riparian “buffer” on each side of the creek as a good starting point, if you have the space. More is better but anything is better than nothing. Work with what you have and feel good about the progress you’ve made; and keep working at it! You and the wildlife will be glad you did.