How far would you travel to get to Dairy Creek?

If you are coming from West Multnomah SWCD’s office, you’d travel about 20 miles north and across Sauvie Island to get to where Reeder Road crosses Dairy Creek at Bill’s Crossing.

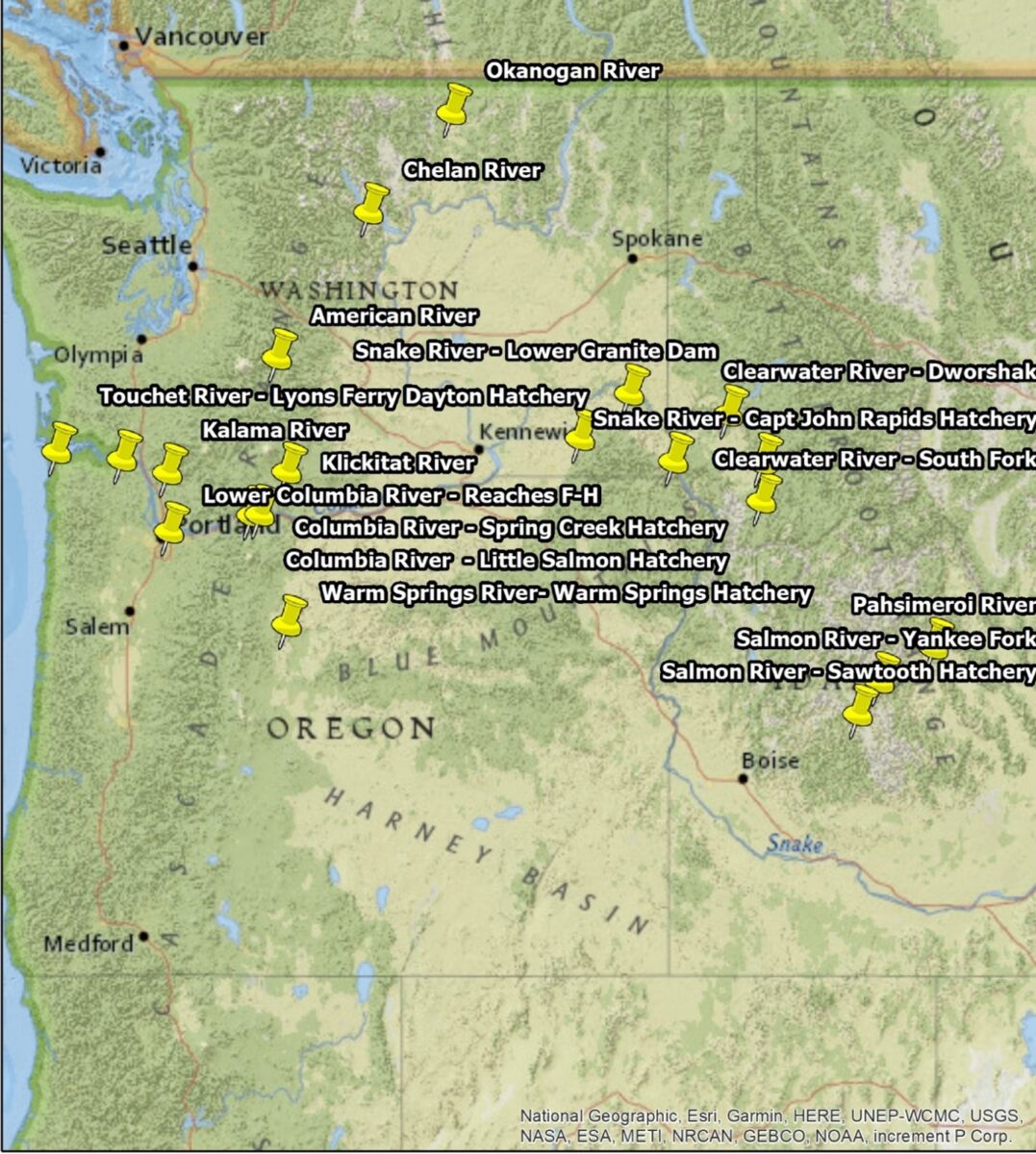

You can’t map swimming routes on Google Maps, but some salmonids (meaning all types of salmon) tracked in Dairy Creek have come as far as Sawtooth Hatchery in Idaho, a distance of at least 400 miles, traveling Northwest. Another traveled over 250 miles Southwest, from Okanogan River in North-Central Washington. See the map above to see all the hatcheries represented in Dairy Creek!

How Many Fish?

Dairy Creek serves as the link between the Columbia River and Sturgeon Lake on Sauvie Island. Witnessing fish returning to this creek stands as an exciting and desired result of that area’s restoration project finalized in 2018. According to a report by the Columbia River Estuary Study Taskforce (CREST) showed a number of fish returning to the area. In 2023, 63 total tags were detected, including 43 Chinook and 3 sturgeon. That is a huge jump up from 2022, when trackers identified 28 tags, and in 21 detections in 2021. 2021 was the first year with the tracking monitors placed.

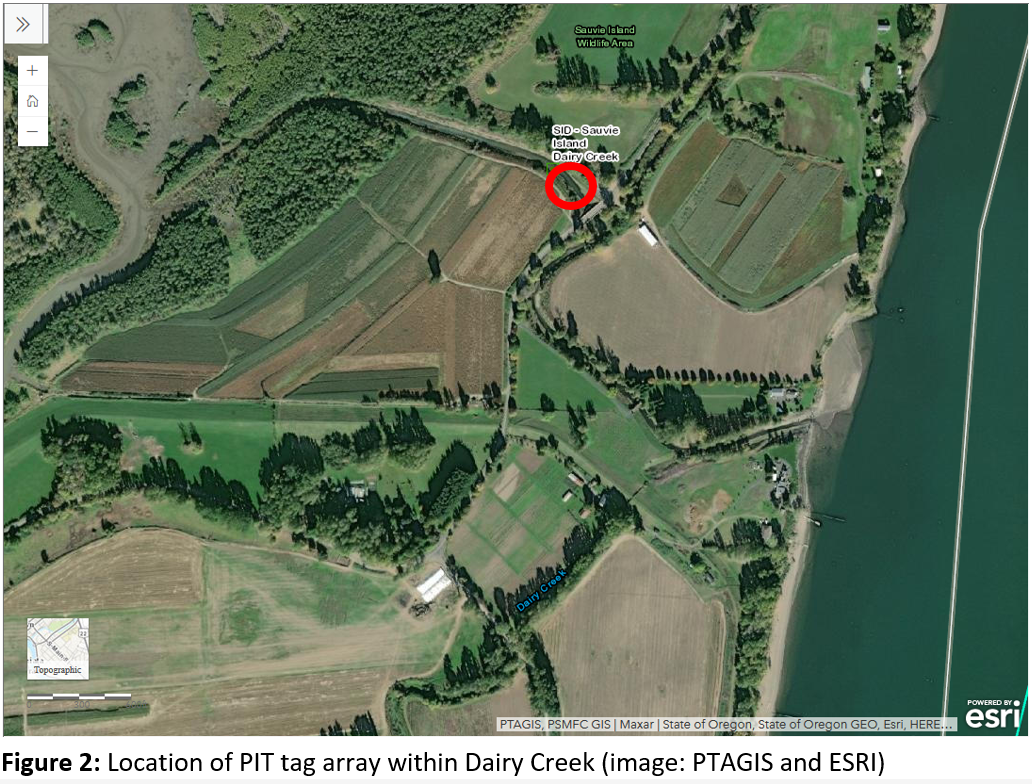

The monitor tracking these fish is PTAGIS, which is accessible online to the public. As of 2024, it has tracked 14 tags (representing fish). CREST has not yet reviewed or reported this data, but we anticipate their 2024 report next year.

Scott Gall, the West Multnomah SWCD Soil Conservationist who has worked on this project since 2008, said that these numbers represent just a small portion of what is actually coming through the Creek. That’s because wild salmon and sturgeon that use the creek are not tagged. He explains that tagged sturgeon represent less then 1% of the overall population, which means the few tagged sturgeon we see probably means hundreds are actually using the channel—more good news for this restoration project.

How Do the Monitors Work?

The monitors consist of antennas positioned in the creek: one set resembles fins detecting fish as they swim by, while the other resembles a rope ladder laid on the creek bottom, detecting fish swimming over it.

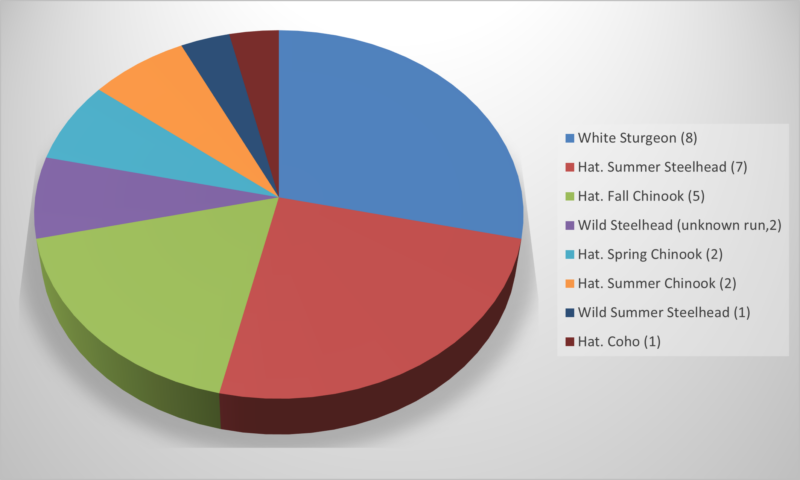

These monitors use embedded tags inside fish to detect the number of fish swimming through the creek, employing the same technology as chips used for household pets. Through that, we also gain exact knowledge of their origin hatchery or fishery, release time, and their specific fish species. For example, “salmonid” is a word that means all types of salmon; in 2023 the most common detected were Hatchery Summer Steelhead (7 fish), and Hatchery Fall Chinook (5 fish, 25%). Four other kinds of salmonid were detected, along with Wild Steelhead (3 fish, not from a fishery), and 8 white Sturgeon.

Why We’re Excited for Fish

This map (top of page) tells us how long fish traveled to reach Dairy Creek. Before, the creek was blocked with dirt from 1996 to 2016. But, thanks to a project by West Multnomah Soil and Water Conservation District and partners like CREST, Bonneville Power, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the US Army Corps of Engineers, now more fish, animals, and plants call it home.

This area was the site of feeding, protection, and rearing for sturgeon and salmonids, so it is exciting to see them back in the area and able to follow their instinctive journeys and find habitat in this area again. These fish are significant to their environments—not just to those among us who love fishing. Salmons’ long journeys help move nutrients throughout streams and rivers and they are a source of food for a number of native animals. Salmon and sturgeon finding habitat again is a benefit to Sturgeon Lake, Dairy Creek, Sauvie Island, and all the waterways the salmon found themselves in before and after their journeys to us.